This is the script for the ‘infinite scroll podcast’ episode: ‘The Rise of Doxxing: How We’ve Normalised The Invasion of Privacy Online.’

Ever since we have existed in the online world, privacy has been a top concern.

From parents warning kids about stranger danger on sites like Omegle, to locking down Instagram accounts– keeping details private has always mattered. And though we are now spending more time online than ever before, it seems like the sanctity around privacy has waned. That doesn’t mean we don’t care about privacy—Gen Z, for instance, is known for being more restrained online, often posting less on platforms compared to Millennials. However, as we get used to social media giants tracking our data, many of us now see privacy as an illusion. And whether that’s actually true, it’s affecting how users treat one another online.

Take doxxing, for example. Associate Professor Carmen Lee explains the phenomenon in a journal articledescribing how doxxing is a form of digital abuse where someone intentionally seeks out and shares a target’s personal information without consent. This type of private information could include anything from their address and full name to their place of work.

The term dates back to 1990s hacker culture, where “doxxing” was shorthand for “dropping documents.” It began as a tactic to expose, harass, or discredit people by revealing private details, often to intimidate or pressure them. Used initially to deanonymize online figures, doxxing became a tool for harassment and even extortion.

While this may have started in hacker communities and circles, it has become increasingly common across the digital landscape. Associate Professor Lee continues by offering her explanation in the journal article, writing: “As society becomes increasingly mediatized, one does not need to be a hacker to retrieve and share information of another person. As soon as someone posts content onto their social media profile, whether it is intended to be shared privately or publicly, they are already prone to exposing themselves to an unknown audience because of the ‘context collapse’ of social media, i.e. the ‘collapse of infinite possible contexts’ into one, with an ‘infinitely ambiguous audience’.”

That being said, doxxing really entered the mainstream through the Gamergate controversy.

Gamergate was a massive harassment campaign in 2014 that targeted women who spoke out against misogyny in gaming. Many prominent women in the industry faced relentless abuse and threats, some so severe that the FBI got involved.

It all started when indie game developer Zoe Quinn released a game called Depression Quest. Soon after, an ex-boyfriend of Zoe posted a lengthy, invasive blog accusing her of cheating with several men in the gaming industry, allegedly to boost her career (unfortunately, this post is still available to read online). One of those men reportedly wrote for Kotaku and was named Nathan. Although Zoe and Nathan denied the accusations, gamers swarmed Twitter, Reddit, and 4chan, claiming this was an “ethical breach” in gaming journalism.

While the Gamergaters claimed they were vanguards of ethical journalism fighting to “expose” corruption by any means necessary, their actions were simply harassment.

In a piece for TIMEfrom 2017, Zoe reflected on Gamergate, how it changed her life, and what the Gamergaters did to her.

“I had been hacked, and someone was in control of my account, broadcasting whatever they felt like to my 17,000 Twitter followers as well as to all the creeps who had been manually lurking on my page,” she writes. “The hackers weren’t just posting calls for me to die or talking about what a fat slut I was; they were sharing my personal information: my old address in Canada, cell-phone numbers from a few years back, my current cell-phone number and my current home address.”

A decade later, the effects of Gamergate linger. Many prominent women in gaming are still wary of addressing it openly, and some publications warn that the industry may be facing a “Gamergate 2.0.” This time, the focus is on Sweet Baby Inc., a narrative development company accused by critics of pushing a “woke” agenda in gaming.

With doxxing becoming increasingly mainstream during Gamergate, it isn’t surprising that this practice would blow up among gamers and streamers– particularly those on Twitch.

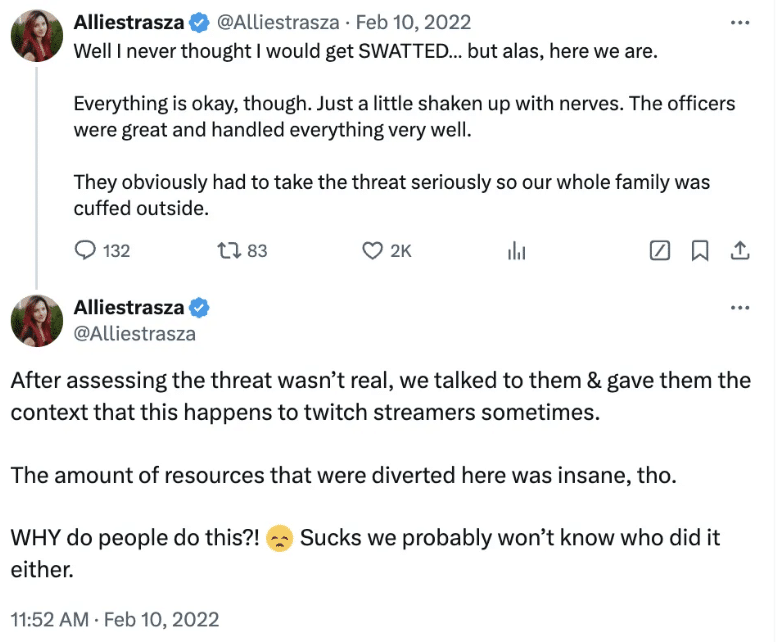

Recently, Twitch has seen a rise in cases where streamers are doxxed and then swatted— a double hit of harassment. While doxxing exposes private info, like home addresses, swatting takes it further: trolls use that info to call in fake emergencies, sending police to a streamer’s home while they are on live.

Recorded live streams of police swattings show how traumatic and dangerous the experience can be. Squads of armed police officers are recorded bursting into rooms, pointing their weapons at streamers, while the creator is obviously caught off guard.

The stream is usually stopped, followed by a tweet from the streamer telling their fans that everything is okay, and that the police had responded to a prank call.

However, not every swatting prank has ended harmlessly, as was the case when an innocent man was tragically shot by police responding to a prank call after an argument between gamers playing Call of Duty World War II in 2017.

Being harassed in such an extreme way, swatting presents a real danger to streamers’ personal safety, not to mention the psychological impacts.

For instance, many streamers have said that they no longer feel safe in their own homes, knowing that their address has been leaked. This has forced many streamers to relocate themselves and their families, no doubt creating a financial burden, and some streamers have been forced to find work outside of full-time streaming all together.

In June 2021, top streamer xQc revealed he had been forced to move back to his native Canada, after his address had been leaked and he was being swatted by police almost daily.

“Almost every day the police came to our house with the full squad […] And I was genuinely scared that I was going to die,” he shared on a livestream.

Former streamer and Drag Queen Jupiter Velvet left full-time streaming after being swatted in September 2021, and told NBC she was left with no choice but to find other work to subsidise her lost income.

Jupiter’s experience is reminiscent of other streamers associated with the LGBTQIA+ community, with many members being frequent targets of doxxing and swatting. Drag queens, in particular, have borne the brunt of these cyber attacks. Through 2021 and 2022, for instance, six members of the drag queen streaming collective Stream Queens were swatted.

Alongside queer people, women are also at a greater risk of doxxing. In an journal article written by Assistant Professor Stine Eckert and PhD candidate Jade Metzger-Riftkin, the academics share that “Women are more likely to receive greater amounts of unwanted, vitriolic, and sexualized messages, to be the targets of cyber-mobbing or brigading, revenge porn, nude leaked messages, and receive unwanted sexualized items.”This is especially concerning because doxxing often happens alongside other forms of online harassment.

With doxxing and swatting affecting countless streamers, it’s become a significant issue for Twitch. Amid mass employee lay-offs to creator boycotts, it’s one of many challenges the platform faces—but probably the most directly threatening to creators’ safety. As a result, the platform has made a concerted effort to restrict doxxing. For instance, it is obvious in Twitch’s community guidelines that doxxing and swatting are prohibited on the platform.

As the community guidelines read: “Violence [including doxxing and swatting] on Twitch is taken seriously and is considered a zero-tolerance violation, and all accounts associated with such activities on Twitch will be indefinitely suspended.” Beyond this, the platform has even restricted sharing information that is available via the public record.

Last year, according to Tubefilter, Twitch added a clause that allows the platform to take action against people it discovers have doxxed or swatted someone in real life or on another part of the internet.

While Twitch has taken action in its community guidelines, the platform hasn’t really managed to stop streamers from being doxxed. Regulation has been difficult, reaffirming just how hard it is to control this type of online harassment and prevent breaches of privacy online. As a result, doxxing is unfortunately becoming common across other platforms.

Case Study: Jacksfilms & SSSniperwolf

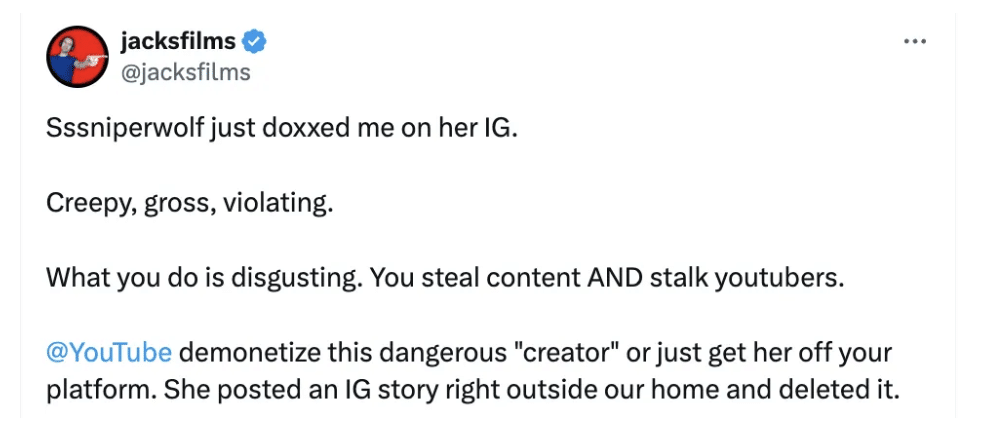

One of the most recent examples of a creator getting doxxed – and going extremely viral for it – actually went down on Instagram and X. It all started in October of last year, when SSSniperWolf—real name Lia Shelesh— seemingly doxxed YouTuber Jacksfilms.

For context, Lia had become known for her reaction-style videos on the platform. Jack had been critical of Lia’s reaction-based content for months previously. He made videos alleging that she stole content, failed to credit creators by blocking their usernames, and even went on to create a second YouTube channel mocking Lia’s content.

Things came to a head when Jack claimed that Lia doxxed him. He shared a screenshot from her Instagram story when she asked her followers if she should “visit” Jack, mentioning that he lived just minutes from her shoot location.

Lia also shared a video on her Instagram story outside Jack’s home. She later defended her behaviour, suggesting it was justified since Jack had consistently posted about her on his YouTube channels, characterising it as “obsessive behaviour.”

“Accusing me of doxxing is literally defamation. I have no idea how to dox,” Lia later wrote on her Instagram story. “He [Jack] literally posted his address on Google and said I threatened him and doxxed him.”

After countless calls to de-platform Lia, YouTube temporarily demonetised her content— meaning the creator didn’t make money from videos uploaded to the SSSniperwolf channel.

According to reporting at the time, Lia’s main channel appeared to be demonised, but her other channels remained unaffected. As a result, YouTube’s attempts to address the situation was not received well.

Users questioned why the platform only temporarily demonetised SSSniperWolf while seemingly attributing blame to both Lia and Jack for the situation. These users believed that influencers like Lia receive “special treatment” and “favouritism” because they bring significant audiences to the platform – something that is seemingly consistent across the social media landscape.

Case Study: Trisha Paytas & Trishyland

Another notable example is when Trisha Paytas was doxxed on her snark Reddit, r/Trishyland. Established in October 2021, the Trishyland subreddit started after Trisha’s falling out with fellow creator Ethan Klein.

Trisha and Ethan co-hosted the ‘Frenemies’ podcast together before Trisha left the show in mid-2021 over an alleged wage dispute. While the subreddit started as most snark communities do, with users posting news and speculation about Trisha (and of course, the occasional sarcastic joke and meme), Trishyland quickly descended into one of the most abusive subreddits on the platform.

Throughout 2022, Trishyland engaged in vicious attacks against the creator which only got worse after she got married and welcomed her first baby. In a YouTube video discussing the subreddit and how it ultimately was banned, Trisha reflected on some of the harmful actions of the community. She said the community posted incredibly personal information about herself and husband Moses Hacmon, including which hospital she was planning to give birth at, her doctor’s information, details about her family members, and payment records on her property taxes.

Trisha also revealed that when she was undergoing fertility treatments, members of the subreddit called clinics around her area telling the facilities not to take Trisha and Moses as patients.

Now, Trisha wasn’t the first, nor the last, person to be doxxed on Reddit.

Another infamous example happened way back in 2014, during what would come to be known as “The Fappening” — when Reddit users began posting naked pictures stolen from Apple iCloud accounts. It was even believed that some of the pictures constituted child pornography. Although these pictures originally appeared on 4Chan, a subreddit called r/TheFappening became the primary hub for sharing them.

Though “The Fappening” was not doxxing in itself—even though it was highly problematic in its own right—some users did seemingly go on to dox those associated with the leak.

With all of these examples in mind, this leaves us with a central question: Is doxxing sometimes warranted?

There is no denying that doxxing is extremely dangerous, invasive and in some instances illegal. But many social media users can’t help but wonder if it is acceptable, especially when the person who is being doxxed did something wrong in the first place.

Of course, no one really deserves to have their privacy invaded or stripped – especially in a space as volatile as social media. When information is shared on platforms like TikTok and Reddit, we have little control over who sees it and how quickly it might spread. With that context, even if a “doxxer” doesn’t intend for millions of people to see someone’s home address or their workplace, it can easily happen.

But when it comes to problematic people and comments,, some users can’t help but think that this tit-for-tat strategy isn’t all bad. Consider what happened with Nick Fuentes over the past few weeks as a case in point for this argument.

Shortly after the US presidential election results, Nick, who is a far-right commentator, posted a disgusting phrase to his over 400K followers on X: “Your body, my choice. Forever.” This tweet inverted the pro-choice slogan of “My body, My choice” to attack women’s reproductive rights.

In retaliation, users across the internet doxxed Nick, sharing his personal information—ultimately leading one woman to show up at his home to confront him.

After his information was leaked, TikTok users started poking fun at Nick’s situation writing “Your House, Our Choice” in comment sections. It’s clear that many women view his doxxing as deserved, seeing it as a form of revenge for the celebration of efforts to control women’s bodies in the United States.

@mamamayamaria And i found my favorite peaches for 10.99 at Costco! Could this Sunday get any better? #fyp #foryou #trending #viral #fypシ #abortionrights #foryoupage #womansrights #democrats #costco

♬ original sound – Nostalgic Beats

While many users agreed with this sentiment, others have questioned whether the internet takes their digital revenge too far, especially when the offender didn’t do anything illegal. Does a “harmful” post warrant your private information being leaked?

There are definitely divided opinions on that question. But internet users seem to agree that Nick should have seen this response coming — essentially because doxxing has become increasingly common over the years, prompting many users to be more careful about what they post online. And with the recent US election still fresh, many women and marginalised communities are deeply concerned about what a second Trump term will bring.

Given that Nick’s content isn’t necessarily illegal and platforms are often slow to de-platform problematic figures, it’s somewhat understandable that some users considered doxxing as the only way to stop his harmful messaging.

Whether you believe Nick had it coming or not, this reaction goes to show how normalised doxxing has become since the rise of TikTok.

Like X and Reddit, TikTok has seen its fair share of doxxing — even before Nick. Another notable example was when TikTok users started doxxing the United States Supreme Court Justices after the overturn of Roe v. Wade in June 2022.

According to reporting by Jules Roscoe for VICE: “Some of the videos share supposed credit card information… Other videos show the home addresses of the five Republican-appointed justices who voted to overturn the decision. Those addresses do show up in public records databases tied to the justices.”

While TikTok attempted to suppress the content and delete the videos, Roscoe notes that other videos continued to pop up, with the information “recirculating through smaller and smaller accounts in the same format: a slideshow of the justices’ portraits, with text over their faces.”

@trashohr I love gen z

♬ original sound – AudioKrystal

This example is particularly interesting because it indicates one reason for the normalisation of doxxing on the platform: Gen Z treats doxxing as a form of protest– a theme that is also clear when considering the reaction to Nick Fuentes.

Since 2020, we have watched as Gen Z has embraced political activism and the pursuit of equality on social media. Through this, Gen Z has essentially changed what it means to be a celebrity. Fame is no longer just about “glitz and glam” —it’s also about standing for change and progress.

With this shift, Gen Z expects their favourite influencers and celebrities to take a stand on key issues and share their political endorsements. When they don’t, the backlash can be intense — we all remember the response to Chappell Roan’s refusing to endorse Kamala Harris. Whether this perception is valid or not, it highlights the fusion of internet culture, social media, and politics. This, in turn, has made the digital space more powerful for political protest than ever before.

There’s no denying the positive side of the politicisation of online spaces. With TikTok democratising fame and political commentary becoming more common, the platform has given historically marginalised groups a chance to challenge racial hegemony and oppressive societal systems that are tough to break down. Doxxing, in some cases, has become a powerful tool to flip the balance of power and privilege on its head.

But it’s also a slippery slope. Beyond the risk of misidentification and the spread of inaccurate details, there’s a larger issue with doxxing and the “no-nuance” culture that’s taken root on TikTok.

Consider a typical TikTok comment section. While comments are often funnier than the content itself, they can also veer into problematic and offensive territory. Whether it’s the anonymity or sheer volume of users on the platform, people often don’t assume the original poster will see their harsh comments.

The conversation around this “no-nuance” culture came to a head last year when a creator named Michelle went viral after saying kindness and consideration for others are part of a broader social contract. While most viewers saw Michelle’s message as a simple reminder of a fundamental aspect of human interaction— that we owe everyone a sense of decency and kindness at face value— some users took issue with her video. They claimed that the creator was advocating for compassion towards individuals who are racist and sexist, while others felt that her message attacked neurodivergent people who have difficulty interpreting social cues.

@michelleskidelsky you can be as contrarian as you want but dont be surprised when people get upset with you

♬ original sound – michelleskidelsky

Michelle later took to the platform to clarify her original video, noting that she was not trying to excuse harmful behaviour. Instead, it was a call for everyone to approach people with a base level of empathy and kindness.

What we can take away from this exchange is how TikTok users seem to prioritise the impact and outcome of their behaviour online, even if it means sidelining values like politeness, kindness, and common decency. For many, the ends justify the means—even if it means bulldozing through these principles.

While this isn’t strictly related to doxxing, it shows us how the crusade for moral superiority underpins TikTok culture. More often than not, this sort of discourse champions social justice and equality, while aiming to amplify the voices of marginalised communities. But that isn’t always the case, especially when the moralising voices come from alt-right circles.

So, when doxxing becomes an option, with real lives, families, and mental well-being at stake, TikTok’s relentless moral crusade can quickly backfire.

Lia Kim, writing for Junkee, highlights an instance where the rush to doxxing on TikTok may have been slightly premature. In April last year, creator Jackie La Bonita posted a video captioned, “Watch my confidence disappear after these random girls make fun of me for taking pics.” The video shows Jackie posing for photos at a baseball game, while two girls behind her flip off the camera and laugh. Soon, the TikTok sleuths found the girl’s names, accounts and even where they worked – where the mounting pressure led them to issue an apology to the creator.

Kim questions whether the girls deserved to be doxxed and harassed by thousands of social media users for basically…photobombing in a rude way.

“We probably all have our moments of rudeness in public, yet we don’t have that moment broadcast to millions of people who find out where we work and try to destroy our lives. On the other hand, we’ve also probably faced moments of rudeness from other people and yearned for some kind of justice,” she reflects. “[Ultimately] It feels like doxxing has become a rather acceptable form of punishment for those who end up in the court of public opinion.”

The fact that the definition of “doxxing” has expanded has also helped this along.

In a piece for The Atlantic, Kaitlyn Tiffany notes how “The word [doxxing] once defined a category of behaviors. Now it expresses an emotion,” in other words, whoever feels like they have been doxxed can claim the phenomenon.

Through the article, she discusses a number of different incidents where creators or public figures have been “doxxed,” noting how the term itself has been “used to describe so many different situations—with varying degrees of sincerity and fairness.”As a result, the “original utility” and definition of the term has diminished.

“[Some] people deploy the word doxxing to refer to any breach of trust, whether or not it results in the dispersal of personally identifying information,” Tiffany explains. “In fandom spaces, doxxing can refer to actions that do little more than make the practices of that fandom visible to a wider audience: I was once accused of “doxxing” Harry Styles fans by tweeting out screenshots of a conversation that happened in a public Discord channel, in which everybody participating was using a pseudonym.”

Therefore, as the definition of doxxing becomes blurred, the ethical concerns around it seem less consequential.

On top of that, there’s a definite sense of power in numbers – something that is amplified by the mob mentality that runs rampant on the app. With the algorithm tailoring content to users, it’s easy to fall into an ‘information bubble’ and become trapped by confirmation bias. Sometimes, this bias leaves us eager dox creators and average users — even when such a punishment far outweighs the offence.

All that is to say, the consequences of doxxing someone can be significant and life-altering.

When information is shared online, there’s no telling how viral it could go, with concerns about who might see it and what they might choose to do with that information. On the flip side, some researchers, like ethics and information technology scholar David M. Douglas, argue that doxxing may be justified in cases of deception– where the only way to show this deceit and reveal the truth is to share information in the public’s interest.

That being said, the ethics around the doxxing that we typically see on social media rarely fall into this framework, and they’re murky at best. What used to be a severe breach of privacy that occurred in rare and extreme circumstances now feels almost commonplace. And while the trend won’t vanish overnight, the debate over when — if ever — doxxing is justified will likely follow everyday social media users and creators for years to come.

Listen to the full episode via the ‘infinite scroll podcast’ on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, and YouTube.