This is the script for the ‘infinite scroll podcast’ episode: ‘TikTok as The New Tumblr: How Social Media (Overtly) Counters The Body Positivity Movement.’

Pop culture has always had a complicated relationship with beauty and body standards.

Take a moment to cast your mind back to the early 2000s (though the problematic exchange between pop culture and body image harks back a lot longer than that). Through this era, we saw women like Jessica Simpson, Kate Winslet and Britney Spears labelled as “overweight” for being a size small instead of…maybe… an extra-extra-small? This messaging left many young girls and women insecure, highlighting the media’s long-standing role in warping our perceptions of beauty and shaping what is considered “acceptable” in society. While Gen Z might romanticise this era — and all the aesthetics that come with it — much of the messaging around body positivity was toxic and harmful.

This largely stemmed from the way beauty standards were dictated – with magazines and consumer brands calling the shots. In the pre-social media era, these large conglomerates decided which celebrities, from Cindy Crawford to Angelina Jolie, were the beauty standard. These women were always presented as flawless, which of course, meant thin (and more often than not, white). By promoting an aspirational beauty standard, companies could convince consumers to buy into whatever they were selling— whether it was a product or a mindset.

As a result, media representation in the early 2000s was narrow and exclusionary— something many of us are all too familiar with. Fighting against this reality, body positivity activists were working tirelessly for these different corporations to embrace diversity.

In a piece for Vox, Anna North details the rise of the body positivity movement, marking 2008 as a turning point on social media. It was at this time when many activists (a majority being women of colour) started posting different photos, essays and poetry across Facebook and Tumblr – attempting to “normalise being bigger.” While this shift was happening online, North notes that mainstream culture was moving toward body positivity around the same time.

“In 2004, Dove launched its now-famous Campaign for Real Beauty, which featured a diverse group of women posing in their underwear,” she explains. “All of the women had hourglass figures, were relatively young, and appeared not to have physical disabilities — still, none was conventionally model-skinny, and a campaign showcasing even somewhat larger bodies was revelatory for the time.”

@design.thumbprint Top 10 most successful marketing campaigns of all time NUMBER 4. Dove “Real Beauty” Campaign. This campaign has been so successful it started ten years ago and still runs today. Key takeaway….this campaign celebrates real beauty with real people. There are no airbrushed models. This fights against the notion of a small percentage of women thinking they’re beautiful. Keeping it real really works #dove #doverealbeauty #beauty #commercial #marketing #marketingdigital #marketingtips #marketingtiktok #marketingagency #marketinghacks #businessowner #business #socialmediamarketing #advertising #branding #fyp #fypシ

♬ original sound – Design Thumbprint

While brands have made strides in promoting inclusivity since then, it often feels like little more than a box-ticking exercise. As social media gained momentum and became the primary culture-driving force, users could chart their own course— rather than having a magazine editor do it for them. This led many to follow creators and brands that embraced diversity. Internet users just wanted to see real people who looked like them. And from a commercial standpoint, it made sense for companies to follow these cues from consumers.

Nevertheless, those who profit from people’s insecurities—namely the weight loss and cosmetic industries—continue to make more money than ever. This isn’t to say that progress isn’t welcome, but rather that inclusivity on social media might be more of a “veneer” of diversity than anything substantial.

But the illusion of inclusivity online was truly shattered in 2020– thanks to TikTok.

Previously, many of us might have suspected that platforms had a hand in shaping what content was promoted. However, their influence wasn’t fully apparent until TikTok started to define the cultural zeitgeist. Platforms had been moving towards algorithm-driven feeds for years— away from chronological timelines and focusing less on posts from “friends” or people you “follow.” But TikTok’s FYP took it to a new level.

We were now being served content specifically designed to keep us on the platform. And if there was one thing new media could learn from old media, it’s that consumers can’t resist the aspirational — consistently engaging with content that promotes an unattainable lifestyle and beauty standard for many.

Therefore, TikTok found itself in a strange position— trying to balance the move toward inclusivity within a media environment that frequently works against it. But with an increasingly analytical and demanding user base, diversity was more of an expectation than an option. This meant that TikTok had to push aspirational messaging in a more subtle, covert way. And of course, this could be done through the oh-so elusive TikTok algorithm.

The way the TikTok algorithm actually works remains a mystery to most of us – with the company refusing to share many details. However, in 2020, The Intercept leaked internal documents from TikTok detailing the posts being pushed out to users.

Journalists Sam Biddle, Paulo Victor Ribeiro and Tatiana Dias revealed that there were “algorithmic restrictions for unattractive and impoverished users.” The documents – that were reportedly written in Chinese and translated into English – showed that moderators were told to suppress content featuring people with “ugly facial looks,” “too many wrinkles,” “abnormal body shape,” or backgrounds featuring “slums” or “dilapidated housing” from appearing in users’ FYPs.

Before The Intercept released these documents, the German site NetzPolitik.org had made similar claims, reporting that TikTok was limiting the reach of users— specifically those who might be identified as disabled, fat, or LGBTQIA+. Allegedly, this was part of a wider anti-bullying strategy on the short-form video app. We all know bullying is an issue on TikTok, but this policy was widely seen as misguided and exclusionary.

“The suppression took different forms: for some users, it meant that their videos were not shown outside their native country; for others, it kept the content from TikTok’s most popular algorithmic feed, the public “For You” page, after they had hit a certain view count. Generally, it was applied to specific videos, but some high-profile users were singled out and given the unasked-for protection,” Alex Hern explains for The Guardian.

After NetzPolitik broke the news in 2019, a spokesperson for TikTok confirmed that the policy had been in place, telling the BBC: “In response to an increase in bullying on the app, we implemented a blunt and temporary policy…This was never designed to be a long-term solution, and while the intention was good, it became clear that the approach was wrong.” The spokesperson then went on to say that the app had removed the policy “in favour of more nuanced anti-bullying policies.”

In 2020, a TikTok representative echoed a similar sentiment to The Intercept, explaining that the policy was part of the platform’s strategy to limit harassment. The representative also stated that the policy had been retired by the time the documents were obtained. However, The Intercept’s journalists remained sceptical, noting that “these documents contain no mention of any anti-bullying rationale, instead explicitly citing an entirely different justification: The need to retain new users and grow the app.”

Since The Intercept’s report, there haven’t been any significant leaks about TikTok’s algorithm favouring certain types of content based on appearances. However, conversations around political suppression and censorship on the platform have been circulating—and with the rise of algospeak, it’s something we’re all familiar with. But we’ll save that for another episode.

Even though the so-called “Ugly Content Policy” has been retired, users still see signs of bias in the algorithm. Many of TikTok’s biggest stars—like Charli D’Amelio and Alix Earle—are white and more often than not, thin. While we, as users, play a role in making these creators famous, the algorithm seems to create a “biased feedback loop” for many of us.

AI Researcher Marc Faddoul offered some insight into this process back in 2020. As reported by BuzzFeed News, Faddoul found that after following a new account on TikTok, users were shown other recommended accounts to follow—often mirroring the same ethnicity and even hair colour of the original profile. In this context, if the most popular influencers are white and thin, it’s easier for another thin white creator to gain followers than for someone from an underrepresented group. And so, the “loop” continues.

While this might not be the case anymore, if TikTok was once boosting creators who looked similar to those already famous, it was even harder for people who didn’t fit the typical (and unattainable) beauty standards to gain recognition on TikTok. And nowadays, the platform is so oversaturated… who is to say that we will ever see another user rise to the same level of fame as someone from the first Gen of TikTok creators.

That being said, when we look at the body positivity niche on TikTok, the biases of the algorithm are clear. Many of the creators that became famous on the platform are conventionally attractive based on Eurocentric beauty standards, and the messaging that was pushed continued to uphold these standards to an extent, as well.

In fact, a 2022 study conducted by US-based academics at Pepperdine and Florida State Universities found that a vast majority of body positivity videos on the app ”portrayed young, White women with unrealistic beauty ideals.”

The researchers note that “approximately 93% of the videos [analysed] embodied Western culturally based beauty ideals somewhat or to a great extent, while 32% of the videos portrayed larger bodies.” On top of this, there have been reports that when curvy women post the same type of body positivity content as more petite women, they are more likely to end up getting flagged for violating community guidelines – only further suppressing this subset of users.

In her piece for Vox, North acknowledges how frustrating this has become for many TikTok users, explaining how: “Many young people today say the term “body positivity” has been coopted by thin, white, or light-skinned celebrities and influencers — the same people whose looks have been held up as the beauty ideal for generations.”

Consider Sienna Mae – arguably one of the most famous body positivity creators to come out of TikTok – as an example.

Sienna skyrocketed to popularity in 2020 after posting dance videos, often filmed when she was sticking her stomach out. Since then, she’s moved away from this type of content, especially after a social media hiatus following allegations of sexual assault and verbal abuse by her ex, Jack Wright.

Nevertheless, when Sienna first went viral at just 16 years old, many comments under her videos were positive. Young girls struggling with eating disorders said that her content inspired them to eat a meal and others said that they felt validated by seeing their body type represented on TikTok.

“For millions of teen girls, Sienna Mae is an inspiration, someone who makes it feel okay, and even aspirational, to let their stomach jiggle while dancing or highlight the parts of their bodies they’ve been trained to feel terrible about,” Rebecca Jennings writes for Vox in 2020.

But, as Jennings continues, Sienna had become part of a trend where “thin women were encouraging followers to have confidence in their own bodies.”

While the type of content Sienna was posting likely had some positive effects, it also led to criticism from users who felt Sienna had co-opted the body positivity movement. Sienna herself had acknowledged this backlash, saying she didn’t want to be the “face” of a movement that wasn’t intended to include someone like her. But through no fault of her own, that is exactly what she would become.

With that being said, Sienna’s rise as TikTok’s leading body positivity creator reflects a deeper issue. While the online world often bills itself as diverse and inclusive, in reality, exclusionary, misleading and aspirational content continues to drive today’s creator economy – just as it always has.

And Tumblr is a case in point.

Thinking back to Tumblr, this platform had some of the most harmful niches on the internet through the 2010s — many of which promoted dangerous messaging around body image.

Tumblr was a cultural touchstone for years, but it also had a much darker side. Many users, particularly tweens and teens, found themselves in circles that glamorised self-harm, mental illness, and eating disorders.

As they scrolled through their dashboards, users were often bombarded with images of thigh gaps, extremely flat stomachs and text posts with troubling mantras. Reblogging and repeatedly seeing this imagery conditioned many young girls to believe that “thin” was the only acceptable body type. This belief gave rise to the “Tumblr girl” stereotype, which was characterised by struggles with mental health and body image. These issues were frequently romanticised as a noble struggle.

The widespread nature of this content was incredibly dangerous — even those who didn’t actively seek it out would still stumble upon it. As a result, many Tumblr users would go on to exist on the fringes, or within pro-ana and pro-mia communities. These spaces, short for pro-anorexia and pro-bulimia, would host blogs that glorified, encouraged, and promoted various eating disorders, self-harm, and other self-destructive behaviours.

The content within these communities was split into two categories: “meanspo” and “sweetspo.” According to Reddit users who were previously members of pro-ana Tumblr communities, “meanspo” was essentially harsh, often cruel statements meant to make users feel bad about themselves and trigger them. On the other hand, “sweetspo” offered a more deceptive form of encouragement, with messages like, “You’re beautiful now, just imagine how gorgeous you’ll be when you’re finally skinny.”

Of course, there were also several extremely thin women and girls who became idolised in these communities as “thinspiration.” One of the more mainstream figures was Eugenia Cooney.

Since 2013, Eugenia has become known for her bubbly personality, cosplay, emo fashion and beauty content, but she has also had to navigate an endless stream of comments and videos expressing concern for her health.

Scrolling through Eugenia’s social media profiles, it becomes clear that she suffers from some sort of eating disorder. While her condition was the focus of a Shane Dawson documentary back in 2019, it’s not a topic she typically addresses in her own content. Though Eugenia’s intentions appear well-meaning (in that she doesn’t directly promote disordered eating), she has always been a polarising figure online.

@eugeniaxxcooney Buzz is so cute! Dogs are the best 🐶💖 #dog #pug #dogsoftiktok #fyp

♬ By the Sea (Highlights Version) – Johnny Depp & Helena Bonham Carter

Throughout her career, there have been numerous petitions for her to be deplatformed, claiming that she is promoting and profiting from her eating disorder given that she has long been popular among “pro-ana” circles – with many users touting her as their “thinspiration.” Critics argue that Eugenia sets a harmful precedent for her followers, especially young girls. This kind of criticism is something that many pro-ana advocates and communities have come up against repeatedly over the years.

While users and platforms have made efforts to limit the reach of these communities, the content is notoriously difficult to monitor. Despite Tumblr’s policies over the years—specifically targeting blogs that “glorify or promote anorexia, bulimia, and other eating disorders”—the content continues to slip through the cracks. The integration of hashtags on platforms like Tumblr have also helped grow these communities, as they allow for easier navigation toward specific kinds of content. With that being said, users often outsmarted moderation by deliberately misspelling popular pro-ana hashtags. Sociologist C.J. Pascoe even likened attempts at moderation to a “whack-a-mole” game, where shutting down one blog simply led to another popping up in its place.

While Tumblr worked to protect the safety of its users through these policies, some journalists and internet users were concerned about the users within these communities if they were banned. Finding like-minded people online can be incredibly powerful—especially during your teen years when everything feels so unpredictable and unstable.

As Kelly Bourdet wrote for Vice in 2012: “Removing spaces for self-harm to be discussed will further alienate those who participate in these behaviors: sure, talking about starving yourself on your Tumblr is unhealthy, but without Tumblr that person may just continue starving themselves in isolation.”

Having said that, pro-ana communities were particularly dangerous because they brought together individuals who were often grappling with, or vulnerable to, mental illness. Rather than offering support through healthy channels like therapy or rehab, these communities frequently encouraged maladaptive coping mechanisms and harmful messaging around body image.

Regardless, if you search for problematic hashtags like #thinspo or #pro-ana on Tumblr today, you’re redirected to a page offering resources for eating disorders. But despite these efforts, users can still choose to “View Search Results,” where the same toxic images and mantras continue to circulate—hidden under clever misspellings like “thynspo” with a ‘y’ or “sk!nny” with an exclamation mark replacing the ‘i.’

When we compare Tumblr and TikTok, it’s clear that TikTok’s negative messaging around body image is much more covert.

Rather than being blatantly “pro-ana,” TikTok has historically promoted harmful body image ideals under the guise of body positivity or algorithmic bias. As journalist Laura Pitcher rightly puts it in a piece for NYLON, “The nature of pro-ana content can often be insidiously disguised as “thinspo” tips or wellness trends to promote healthier living…This means teenagers may be exposed to pro-ana content without realizing.”

Pitcher points out how specific trends like “What I eat in a day” videos and OOTDs can sometimes have harmful effects. With wellness culture being such a major part of social media these days, she highlights how difficult it can be to distinguish between “pro-ana” eating diaries and those that simply promote healthy habits.

Additionally, GRWM videos or OOTDs often involve bodychecking— that is, the compulsive act of scrutinising your body by taking pictures or videos while also hoping to gain feedback on your body from others. Bodychecking isn’t a new concept, but it has become increasingly common on TikTok, subtly reinforcing unhealthy habits under the guise of everyday content.

This kind of covert messaging continues on the platform. However, over the past few years, there’s been a shift—more overt pro-ana content has started to make the rounds on TikTok.

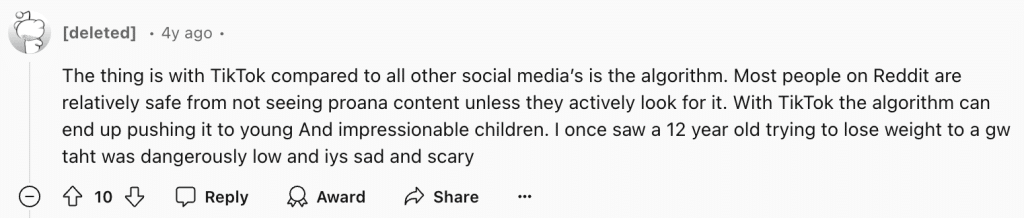

To avoid spreading inaccurate information about these communities, we’ve looked to various online threads where people familiar with this side of the app have shared their insights. Browsing through Subreddits specifically, we’ve seen a number of posts from users asking why “anorexia [is] becoming a trend on tiktok.”

In one of these threads, users pointed out that most of the pro-ana content they encountered on TikTok appeared coincidentally—highlighting just how powerful the algorithm is and how easily it can lead users down dangerous rabbit holes.

Thanks to these algorithmic biases, the FYP can send viewers down dangerous paths. Even though TikTok’s algorithm remains somewhat of a mystery, many of us have figured out tips and tricks to tailor it to our preferences, whether that’s by clicking “not interested” or engaging with certain videos. Despite that, the algorithm is constantly learning from our behaviour—what we like, comment on, follow, or how long we spend on a video—and uses this data to serve us more of the same type of content.

In terms of how the algorithm can lead users toward pro-ana and other related ED content, fitness and wellness reporter Talya Minsberg explains the slippery slope in a piece for the New York Times: “If a teenager searched for healthy snack ideas or interacted with certain cooking posts, a platform may then serve videos about low-calorie foods. That may signal an interest in weight loss — and soon, that teenager might see advice for restricting snacks or tips for crash diets. A user’s feed could then be filled with posts supporting unhealthy behaviors, or celebrating one body type over others.”

Some of these TikToks might include low-calorie food ideas, “sweetspo” or “meanspo” edits, and weight loss progress stories. On the flip side, it may also show recovery-oriented creators – many of which Reddit users have praised as a source of inspiration and support within TikTok’s ED-centric communities. Despite these positive influences, toxic content still persists, revealing just how challenging it is to moderate and control this kind of messaging on the platform.

“While there’s a great ED recovery community there, there are a few really toxic people. I remember one of my comments being “bodychecking on the #EDrecovery tag for what” because there were girls who would claim to be recovered and then post videos of literally their collarbones, or just focusing on their waist,” another Reddit user added.

22-year-old Liv Schmidt is an example of one such “toxic” creator on TikTok. Liv is a NYC-based creator who rose to fame this year by sharing her devotion to staying thin– with video topics like “6 things I do to stay thin” and “how to not let yourself go while working a 9-5 job.”

Despite having no health and fitness qualifications, Liv gained over 670K followers for creating shock-value content about weight and dieting– but it was her overtly harmful language and very open fat-phobia that propelled her to viral status so quickly– a strong tell that we maybe not progressed as much as we might have thought from the 2000s Tumblr era. Though Liv was recently deplatformed from TikTok, it took months for the app to do anything about her content and the damage was already done.

Like Tumblr, TikTok faces issues with harmful content slipping through moderation. TikTok community guidelines officially prohibit “showing or promoting disordered eating and dangerous weight loss behaviours.” Through 2020 and 2021, the platform restricted weight-loss ads and introduced a feature that provided helpline numbers to users searching for eating disorder-related hashtags. In 2022, TikTok pledged to remove videos promoting disordered eating behaviours like short-term fasting and excessive exercising. However, by 2023, researchers and experts were still criticising TikTok for failing to protect young users from content encouraging eating disorders.

That is to say, pro-ana content has always been present on the platform, but it has gained noticeable momentum in recent months. There are a couple of reasons for this.

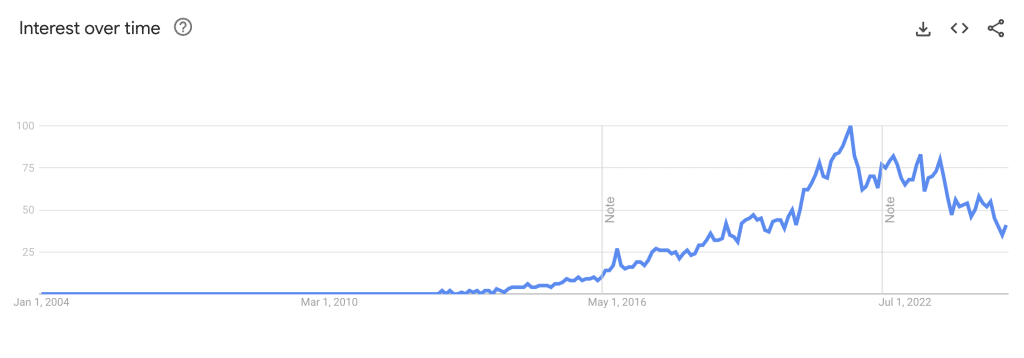

As a culture, we have shifted away from body positivity content. While diversity remains important and body-positive communities still exist across social media, the overall visibility of positive messaging around body image seems to be fading.

This isn’t exclusive to TikTok – Google Trends data shows that global searches for body positivity have been on the decline since May 2021. While this could be partly due to increased familiarity with the movement, there are also some more insidious factors at play.

For instance, the body positivity movement really went mainstream as a rebellion against the beauty standards of the early 2000s, often referred to as “heroin chic.” Thinking back to this era’s ‘it girls,’ the ideal body was designed with thin, white women in mind — Paris Hilton and Kate Moss are some notable examples.

While body positivity helped show the beauty of different body types, skinniness never really went “out” of style. Over the past year, it has noticeably resurfaced, accompanied by the revival of early 2000s fashion trends like low-rise jeans, micro mini skirts, and crop tops. As these fashion trends re-entered the cultural zeitgeist, it was only a matter of time before the beauty standard of the early noughties would return.

This return to “Y2K Skinny” has coincided with the Ozempic drug rush— an insulin regulator for pre-diabetic people whose primary side effect is fast and dramatic weight loss. Ozempic made waves on TikTok last year when the hashtag #MyOzempicJourney blew up, and later again when Kim Kardashian dropped a significant amount of weight in a short period of time to fit into Marilyn Monroe’s dress for the Met Gala. Many now call the drug Hollywood’s “worst-kept secret” because apparently, everyone’s in on it.

Body shapes should never be treated as a “trend,” but with celebrities and influencers going to extreme lengths to fit into the illusion of thinness, it is unsurprising that there has been a noticeable rise in eating disorder content online.

In this new era, TikTok seems to be stepping into the role that Tumblr once held. The platform’s algorithm guides users through various niches and seemingly favours certain body types, making it easier than ever to encounter pro-ana content.

While the format may have moved from static images to short-form video, one unfortunate truth remains: this is just the latest chapter in an ongoing issue that neither platforms nor users have fully figured out how to navigate safely—a problem that continues to leave social media users, many of them teens and tweens, suffering in its wake.

Listen to the full episode via the ‘infinite scroll podcast’ on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, and YouTube.