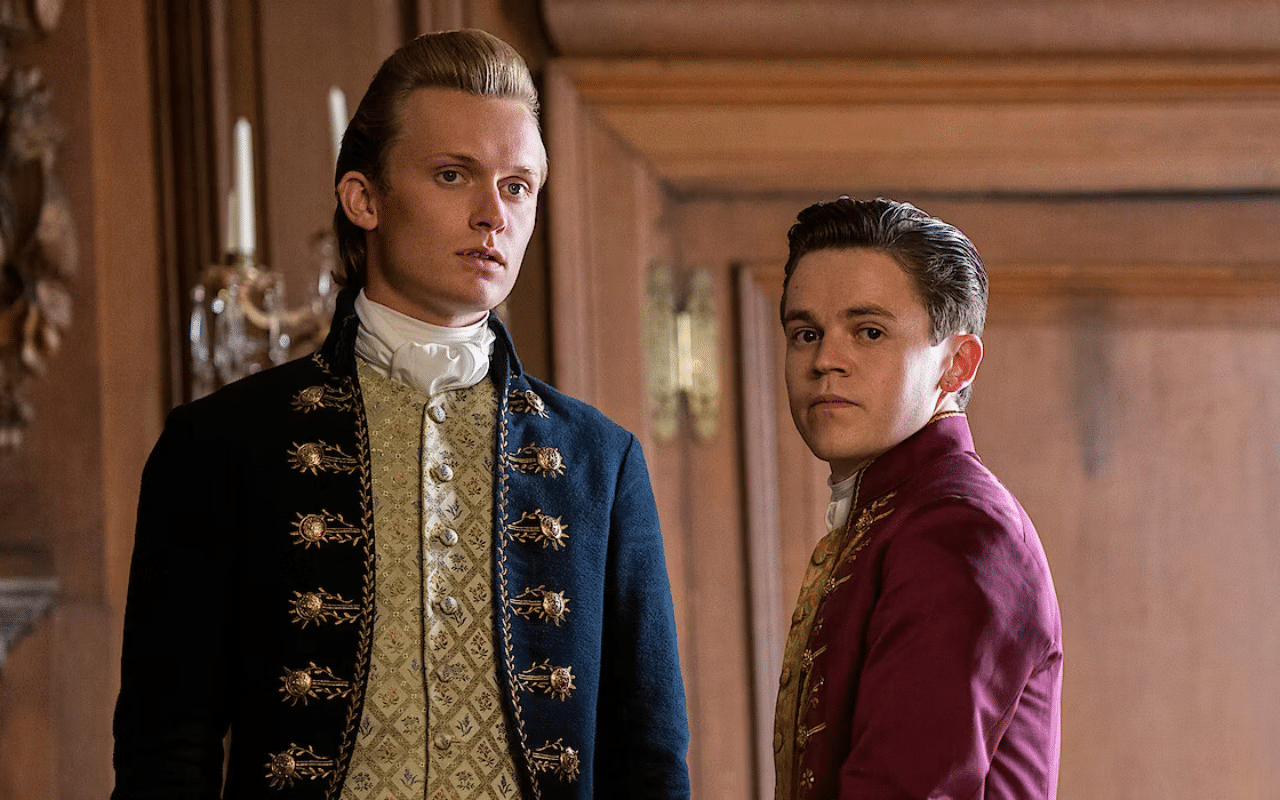

As a fan of Bridgerton and a queer TV critic, I was excited to see a canon queer couple on the spinoff show Queen Charlotte between the Queen’s man Brimsley and the King’s man Reynolds. Unfortunately, as much as I love what we got of their story, it still feels like Queen Charlotte and Bridgerton writ large are not yet willing to go all in on queer romance— coming up short on the spice factor, keeping the queerness to side characters, and worst of all, cutting their story abruptly short without giving the audience any resolution as to what happened to separate the pair in the end. Ultimately it feels like I love Brimsley and Reynolds more than the creators of Queen Charlotte do, who seemed to be throwing the gays a bone while using the couple for a handy exposition of the lead straight pairing rather than allowing them to have a fully realised story of their own.

While I enjoyed Charlotte and George’s journey, the banter-filled story of Brimsley and Reynolds is the one that kept me coming back for more. The pair steal just about every scene they’re in, whether together or alone, and the “behind the scenes” nature of their work adds an upstairs/downstairs element to Queen Charlotte. They form the connective tissue between not only the royal couple but between so many of the other characters, bringing disparate storylines together. Brimsley and Reynolds add so much to the show, and this backstory feels like it will add more to future seasons in terms of Queen Charlotte and Brimsley’s relationship as well as our general love of Brimsley, though I’m also holding out hope for an eventual resolution about what happened to Reynolds.

Getting a canon queer couple in the Bridgerton world feels long overdue, considering how queer some of the main characters read in their on-screen renditions since the jump. Lady Danbury serves soft butch Regency chic. Benedict flirted with queer artist Henry Granville all throughout the first season, to the point that many viewers were genuinely shocked to find out in season 2 that he’s straight. Then there’s Eloise, who’s vehemently uninterested in the heteropatriarchy and the marital industrial complex, but who has a deep connection with her friend Penelope.

I’m still holding out hope for Lady Danbury’s future queer adventures between the two timelines. But how long is Bridgerton going to make us wait? On a show that has pushed beyond the source material for more diversity (albeit with mixed results), why not keep pushing to make the show more reflective of its audience? Why shouldn’t we all get happily-ever-afters?

Not according to showrunner Chris van Dussen. TV Line reported that when asked about Benedict’s sexuality, he said, “It was a conscious choice not to have it be fluid in Season 2.” It’s a disappointing answer that flies in the face of both the season 1 characterisation, and so much of the Bridgerton fanbase. For his part, actor Luke Thompson seems a bit more open, telling Town & Country, “Benedict is clearly a very open character and that’s extremely fun to play. And I think that it’s not narrowly sexual… he’s just a very open person, full stop.”

That said, Thompson still defers to the writers: “I tend to think that’s a question for the writers, really, because in order to be playing a character, I sort of have to surrender that side of my brain. The writers are like God, as in I just have to play with what they give me. I think there is that openness, which is really lovely to play with, but in terms of where it goes, I don’t know.”

There have, however, been a few queer characters in the Bridgerton universe. Artist and dilettante extraordinaire Henry Granville is the best example, as well as a few other unnamed background queers reveling at his after-hours bacchanale, including one man with no lines whom Benedict spies Granville with. But after all that flirting, Benedict ends up having a threesome with Henry’s wife and another woman during those same revels, and Henry disappears between seasons. In season 2 Benedict dated the modiste, Genevieve Delacroix, in a random move that felt mostly driven by the writers’ need to provide his character with a beard and her with an alibi for not being Lady Whistledown.

Between showrunner Chris van Dussen’s line in the sand about Benedict and the few queer characters that do exist having small parts before disappearing, it feels an awful lot like in the world of Bridgerton, queerness is for side characters only. A whimsical artist who will be in a few episodes and vanish; a man with almost no lines? Sure! Actual Bridgerton sibling? It’s “a conscious choice” not to have Benedict be sexually fluid in season 2. It doesn’t help that the Queen Charlotte script made sure to clarify early on that George’s rejection of Charlotte wasn’t because he’s gay – having Reynolds not-so-casually drop that George’s type is “female” was…a choice.

Then there’s the way that the Queen Charlotte script underserved the Reynolds-Brimsley pairing, largely using them as living expository devices and once again giving us a case of a mysterious disappearing queer. The transition from the pair dancing in the past to Brimsley dancing alone was heartbreaking, but is ultimately without context. What happened to Reynolds? In perhaps the most insulting blow of all, it doesn’t feel like a cliffhanger, but rather like a scene was left on the cutting room floor. Apparently, there was a scene they never filmed that was meant to give more context (though it raises as many questions as it answers), but it just makes the pair feel so disposable for the creatives to decide it was fine to leave Reynolds and Brimsley’s story unfinished in such an unsatisfying way.

At its best, Queen Charlotte allows some of Bridgerton’s most compelling featured players to step out from their roles and be the star of their own stories. Violet gets to explore how she feels about romance and sexuality as an individual rather than as a mother and grandmother. Even if the answer is that she’s not yet ready for a new connection, it’s a choice that she’s made for herself, not for anyone else, and there’s a sense that she may be open to it in the future. So much of Charlotte’s story is about how she was forced into situations against her will, yet she finds a way to assert agency and create a path forward that works for her, her husband, her community, and her people. But Brimsley and Reynolds are not afforded the same treatment.

When it comes to the world of Bridgerton, the sex scenes are always part of the conversation. Brimsley and Reynolds’ first and only sex scene was promising – lots of tension and urgency, a bit of butt cheek, and the suggestion of oral sex. But after that, everything was rather chaste. At most we got banter, attempts at hand-holding, a dance, and domestic scenes of post-coital arguments or bliss, cutting off just before or picking up just after the action, often using them for exposition more than anything. Compare Brimsley and Reynolds’ time in the bath with Charlotte and George’s. Their bath scene would be fine for another show, but this is the franchise where heteros have sex on stairs, in the rain, or have a pulling-out montage. Queen Charlotte cruelly made time to show Lady Danbury being violated over and over again, inexplicably playing it for laughs and adding to the Bridgeton universe’s poor record on sexual assault of its Black characters. Yet there was only time for a queer couple who (consensually) can’t keep their hands off of each other to have one sex scene?

This is hardly the first show to keep queer sex scenes to a minimum. The history of relying on implication and innuendo when it comes to the sex lives of queer men, especially, is about as long as the history of television, and it ties into decency regulations, including those self-imposed by networks. The first kiss between two men on primetime television was only in 2000, on Dawson’s Creek. Since then, things have improved somewhat, but it’s still more common to see intimacy on screen between cishet couples, and even queer women pairings, than it is between men. On Modern Family, Cam and Mitchell famously only shared the occasional peck on the lips, even when they got married. Even more sexually explicit shows like Game of Thrones, which was the inspiration for the term “sexposition,” have shown queer pairings with less nudity and fewer actual sex scenes than hetero couplings.

For all that I enjoyed watching Reynolds and Brimsley, the shortcomings of how their pairing is portrayed, including the final insult of cutting off their story so abruptly, is illustrative of how the Bridgerton franchise as a whole has treated queerness. It’s been three seasons across two shows, Bridgerton – we’re tired of waiting.