This is the script for the ‘infinite scroll podcast’ episode: “Celebrity Blind Items: The History, Popularity & Ethical Implications of Unverified Claims.”

Over the years online, most of us have probably come across a blind item at some point, even if we didn’t realise it. These pieces of gossip about public figures—where everyone involved stays anonymous—have become a big part of celebrity culture. Whether it’s about a pop star’s relationship status or an influencer’s financial struggles, blind items cover it all—and no public figure is off-limits.

For those who aren’t fully familiar with blind items, it’s just what you’d expect. It’s not your typical gossip or news where we know exactly who or what is being talked about. Instead, it’s more like a riddle or puzzle, dropping hints about a person or situation without revealing all the details. The clues could be something as vague as “A-list YouTuber” or “actor/writer/director,” or more specific, like “the influencer behind a coffee company,” which many of us would instantly link to Emma Chamberlain.

There are several reasons why someone might choose to leak a story through a blind item instead of using a name. It could be a fear of being sued by a celebrity for defamation, not wanting to be the whistleblower, or simply avoiding the heat that comes with making such a claim. Whatever the reason, these posts have given pop culture enthusiasts unprecedented insights into celebrities and their lives—or perhaps more accurately, the lives we’ve created for them.

Origins of the Blind Item

It’s well-established that the blind item originated in the early 19th century, initially used as a form of blackmail. However, the exact origins of the blind item remain unclear. Some sources suggest it began across the Parisian press. However, a majority credit a man named William d’Alton Mann, who published a magazine called Town Topics in New York, as the pioneer of the phenomenon. Town Topics was probably the equivalent of today’s gossip magazines—think People or Page Six.

“[Town Topics] was a weekly magazine equally loathed, loved, and feared by the moneyed class of the Gilded Age,” Joe Pompeo writes for Town & Country Magazine. “Under Mann’s stewardship, Town Topics became both a trenchant chronicler of the one percent and a vehicle for Mann to join its ranks. Members of the elite… paid sums with the expectation that Mann would keep their peccadilloes out of his publication”

Since then, blind items have gone through brief periods of revival. In a 1970s edition of Ladies’ Home Journal, American novelist and screenwriter Truman Capote noted that blind items were particularly popular in the 1930s and 1940s, for instance. But the modern obsession with blind items really took off in the 90s, fuelled by the rise of gossip blogs and tabloids.

The 90s and 2000s were a transformative era for pop culture with the birth of blogging. While not all of the iconic blogs focused solely on celebrities, many became the go-to source for inside scoops about the most popular stars. Blogs like Gawker—launched in 2002—and outlets like TMZ, Just Jared, and Perez Hilton, all of which opened in 2005, were relentless in covering celebrity relationships, rumours, and scandals.

Blind Items in the Online World

Dubbed the “Tabloid Decade,” the 2000s saw celebrities relying on these outlets for visibility, even as the attention often crossed into invasive and uncomfortable territory. Women, in particular, were frequently trapped in a harsh cycle of public scrutiny.

But by the mid-2000s, as Anne Helen Petersen wrote for BuzzFeed News, celebrities had become “largely beholden” to paparazzi and gossip blogs. And blind items had become a key tool for these outlets to share controversial—or outright unverified—“news” without risking legal backlash, cementing their place in an increasingly ruthless gossip ecosystem.

“In the ’90s, the blind item enjoyed a renaissance in juicy celebrity columns like Page Six and the Village Voice, which published anonymous, unconfirmed bits of gossip concerning the rich and famous that would be sure to get readers talking while the publication itself could steer clear of any potential lawsuits,” Rachel Brodsky writes for the LA Times.

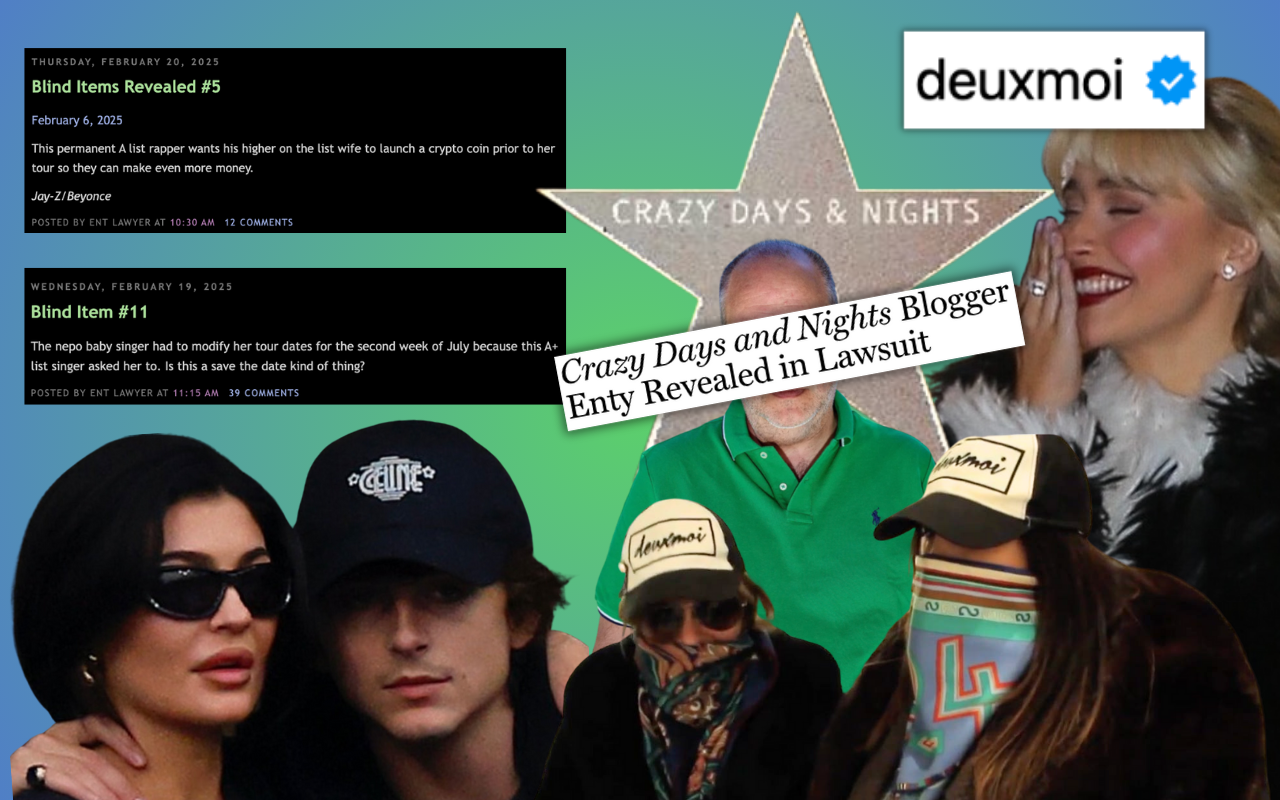

But in 2006, blind items reached new heights of popularity with the launch of Crazy Days and Nights. The blog would cover anything from sexual transgressions to drug addictions to corruption in the industry. Its founder, known as “Enty,” claimed to be an entertainment lawyer but kept his true identity a mystery for nearly two decades.

In a piece for Vulture, Lila Shapiro cited Enty’s first post to explain why he created Crazy Days and Nights.

“In his first post, [Enty] wrote that he’d started the blog because he was in a ‘unique position of being able to tell you what really goes on behind the scenes and what even the gossip magazines can’t find out’,” Shapiro shares.

His access seemed impressive, and he quickly became an icon in the gossip world. So much so that Vanity Fair declared Enty “The King of The Blind Item” in 2016.

“[Enty has] been a direct source for gossip that evades the normal channels of celebrity news and feeds directly into the Internet’s never-ending appetite for the juice,” Mehera Bonner writes for the publication. “But his primacy in the field is largely due to the one feature of his publishing ethos that completely distinguishes him from his rivals: He names names.”

While Enty managed to stay anonymous for most of his career, it all went awry during a messy legal dispute last year. The story begins with a woman named Cassandra Crose—a fan of Crazy Days and Nights and an aspiring podcaster. Enty would eventually go on to work with her, but their professional collaboration soon turned personal. Enty assured Cassandra that he was single, despite actually being married. When Cassandra uncovered the truth and Enty abruptly ended their relationship, she threatened to expose his identity.

To prevent further fallout, Enty filed for a restraining order against Cassandra—a decision that only escalated the drama. Cassandra retaliated by starting her own podcast, where she detailed their affair and accused Enty of being manipulative and abusive. On her Patreon, she shared explicit messages he had sent, igniting an even bigger scandal that ultimately unmasked the creator to be a man named John Nelson.

“Internet sleuths, and eventually a reporter for the Daily Beast, dug up the court documents he’d filed and confirmed that Nelson was in fact Enty Lawyer. And so the gossip blogger became the gossip,” Shapiro continues.

Of course, Enty wasn’t the only one capitalising on the growing interest in blind items. Around the same time, Lainey Gossip was also making waves. It started as an email among friends in 2003 and gained popularity through word of mouth. Eventually, it launched as a website in 2004 and has maintained popularity ever since.

While magazines and blogs might have been the original homes of the blind item, the format feels perfect for social media. The internet’s love for tea—whether true or not—is no secret, and platforms like Instagram, TikTok, and YouTube have given blind items a new life. This shift has paved the way for accounts like Deuxmoi to thrive.

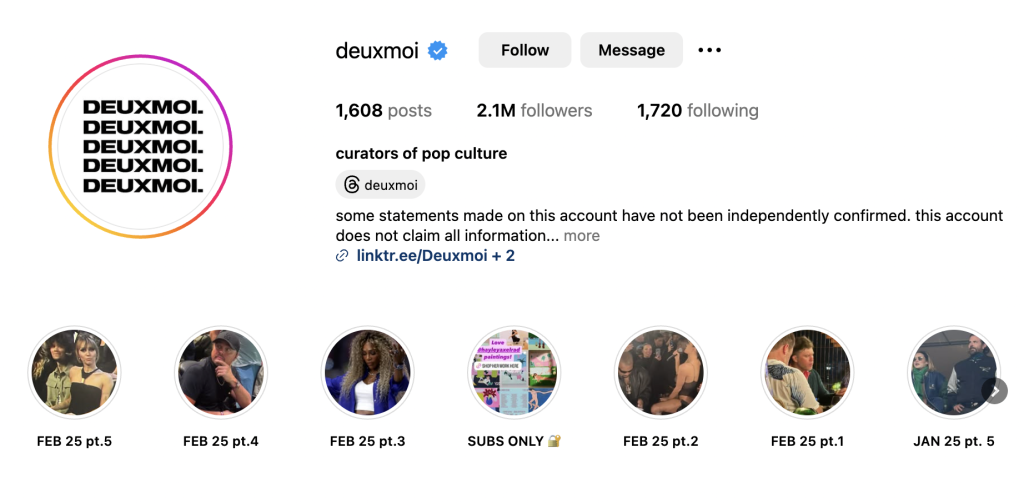

Deuxmoi skyrocketed to virality at the beginning of the pandemic. Originally a lifestyle blog created by two friends, the account posted style inspiration and pop culture memes. But this soon changed. After asking her (approximately) 45,000 Instagram followers for celebrity gossip during the early days of COVID-19 lockdowns, Deuxmoi went viral for reposting the responses on her Instagram story.

Fast forward to today and Deuxmoi boasts over 2 million Instagram followers with subreddits and Facebook groups that exist to discuss all of her updates.

Much like a modern-day Gossip Girl, Deuxmoi thrives on follower-submitted tips, with user-submitted “blind items” becoming a favourite among fans. These blinds tap into the thrill of detective work, allowing followers to speculate and engage in fan-level discourse.

What truly sets Deuxmoi apart, however, is how the account democratised gossip. By empowering her audience to both submit and interpret information, Deuxmoi has made celebrity news a collective experience. Once a “blind” is posted, fans rush to TikTok and Reddit, dissecting clues and guessing which A-lister might be involved. This not only fuels user engagement but also serves as a “get out of libel free” card for Deuxmoi, shifting the responsibility for speculation onto her followers.

For a long time, Deuxmoi’s own identity was shrouded in mystery. But in May 2022, the veil was lifted. Internet culture reporter Brian Feldman did some sleuthing of his own, revealing on Substack that Deuxmoi was run by two women: Meggie Kempner, a fashion designer and the granddaughter of socialite Nan Kempner, and a woman named Melissa Lovallo.

In addition to TikTok users discussing blind items from accounts like Deuxmoi, some have seized the opportunity to turn their obsession with blinds into full-fledged influencing careers. A popular example is Shannon McNamara. She rose to fame by relaying blind items and offering timely analysis on pop culture. Her insights into the latest celebrity gossip and theories eventually led her to launch her own podcast, Fluently Forward, where she discusses everything from pop culture to conspiracy theories and, of course, more blind items.

Another example is the TikTok account @celebriteablinds_, which posts blind items daily. While this account has less of a “personality” or creator presence than Shannon, it still capitalises on the same fascination with celebrity gossip, giving users a steady stream of blind items to dissect and discuss.

All that is to say, that the blind item has a storied history. While it’s always had a certain intrigue, it’s clear that Gen Z has reignited the obsession with this type of gossip and information-sharing—and we’ve got a few theories as to why.

The first is the oversaturation of the celebrity brand & the growing transparency of the celebrity PR machine

Celebrities have always been treated as businesses, but today it seems to be happening more than ever. Rising consumerism, social media, and a growing hunger for representation have intensified the commodification of celebrity. These days, every aspect of a celebrity’s identity—from their style to their personal life—has become a marketable product. Celebrities, whether they’re singers, actors, or influencers, are increasingly seen as corporations and branding opportunities rather than individuals, shifting their primary role from creating art to generating profit.

A prime example of this is the rise of the pop star “era”—and no, this is not just limited to Taylor Swift. From the likes of Ariana Grande to Billie Eilish to Sabrina Carpenter, artists differentiate between albums and tours with carefully curated aesthetics. Think of Ariana Grande’s latex bunny ears from her Dangerous Woman album or Sabrina Carpenter’s kiss motifs through the Short & Sweet tour. These visual markers create instant recognition for an “era.”

As for why these eras are important for the artist, Tyler McCall writes for Elle, “creating and revisiting these visually disparate eras isn’t just useful in distinguishing album cycles, it also creates a fuller picture of the artists themselves. Fans feel more connected to a multifaceted musician.”

Taylor Swift has undoubtedly elevated the concept of the “era” with her Eras Tour, turning it into a cornerstone of modern celebrity marketing. With this, art and branding have become inseparable, with a celebrity’s brand becoming the product.

This phenomenon isn’t limited to the pop music scene, either. More and more, we see actresses method-dressing to align with their roles, transforming press tours into carefully-curated extensions of their on-screen characters. Take the recent Barbie and Wicked press tours as prime examples. From head-to-toe pink outfits to green-themed looks, these campaigns illustrate just how vital this strategy has become for building hype and keeping audiences engaged.

@9honey Wicked stars Ariana Grande and Cynthia Erivo have sent fans into a frenzy with their wholesome moment at the Sydney premiere. 🪄👑 #arianagrande #wicked #yellowbrickroad #cynthiaerivo #sydneyaustralia #australia #wizardofoz

♬ Dance You Outta My Head – Cat Janice

However it is important to note, this has always been a thing. But these days we are much more attuned to it than before, and part of this comes down to COVID.

COVID-19 stifled most of Hollywood’s age-old traditions. With award shows cancelled and red carpet attendance restricted, the business of being a celebrity was effectively shut down. Even as the constraints of the pandemic eased throughout 2021 and 2022, by no means was the world totally back to ‘normal.’

This shift brought about two key changes that arguably fuelled the rise of blind items in popular culture.

First, lockdown expanded the scope of “interesting” celebrity gossip. With the entertainment world grinding to a halt, so did the salacious celebrity gossip that we had become accustomed to. So, celebrity gossip enthusiasts had to adapt to a world, where honestly, not much was happening. And with that, what constituted celebrity news became surprisingly un-newsworthy.

Consider Deuxmoi as an example. During COVID, she thrived on reposting celebrity sightings from her followers. Her Instagram highlight was full of tips like, “Hailey and Justin Bieber sitting next to us now” or “Kim K is at CVS.” Ultimately, celebrity gossip became less about breaking a major story and more about documenting everyday moments – broadening the scope for blind items.

Secondly, lockdown gave us plenty of time to step back and analyse celebrity culture and its PR machine with some distance. This only intensified with the rise of TikTok and the popularity of PR and marketing-focused creators like GirlBossTown—whose real name is Robyn DelMonte.

@girlbosstown Reply to @haleyspeaks_ #greenscreen #taylorswift

♬ original sound – GirlBossTown

Robyn skyrocketed to virality with her breakdowns of celebrity trends and her marketing advice, giving everyday users a behind-the-scenes look at how celebrity PR works. She helped demystify PR moves, showing how celebrities and brands strategically plant stories or manipulate narratives. This, in turn, has left many TikTok users to become more sceptical of the way celebrities share information, with many of us now aware that a lot of what we see is carefully curated.

That brings us to our second theory, the rise of misinformation and citizen journalism across social media has fuelled interest in blind items.

To be clear, misinformation and citizen journalism are two distinct phenomena, but together they’ve played a role in the rise of blind items and our growing tendency to believe them— no matter how untrue each story might sound.

It is first worth discussing citizen journalism and its impact. Put simply, citizen journalism refers to everyday people— a.k.a non-professional journalists—taking on the role of reporting news or sharing first-hand accounts of events. Platforms like TikTok have made this easier than ever, democratising who gets to tell a story and giving the average user a platform to cover news or serve as primary sources. This shift has clear benefits: it brings attention to underreported events and amplifies marginalised voices often ignored by traditional media.

But there’s a catch— or two. First, the rise of citizen journalism has widened the trust gap between audiences and traditional media. When citizen journalists cover stories that mainstream outlets ignore— or when they frame issues in ways that feel more authentic— it deepens scepticism toward traditional media and the publication process. This distrust often extends to how mainstream outlets report on celebrity news, also making people more willing to buy into the whispers and speculation of blind items.

Second, while citizen journalists can offer valuable perspectives, they’re not held to the same standards as established media outlets. This lack of editorial oversight means their reports can sometimes include unverified or incomplete information. While this may be unintentional, the impact can be the same as spreading misinformation or disinformation. That is not to say that these mistakes can’t happen in established newsrooms or within traditional mastheads, but rather that certain guardrails and processes are put in place to limit the spread of inaccurate reporting.

As we move away from these media sources, audiences are seeing more and more content that may not be as thoroughly researched, edited or verified. Of course, this isn’t true of all citizen journalists or newsfluencers creators. Many work extremely hard to ensure the information they share is accurate. But the normalisation of this type of content has let audiences grow accustomed to consuming unverified content, which ultimately primes them to accept even more speculative forms of storytelling— like blind items.

On top of this, as misinformation and disinformation become increasingly pervasive online—not exclusively among citizen journalists and creators, of course—the line between verified news and rumours keeps getting thinner. The rise of misinformation online has been analysed to death by social media experts and commentators, but many argue that the downfall of Twitter— now X— was the final nail in the coffin.

Elon Musk’s takeover of Twitter has drastically altered the platform, and not for the better. From enabling anyone to purchase verification to allowing bots to flood timelines, these changes have supercharged the spread of misinformation. This marked a major loss for online news culture, as Twitter had once been the go-to platform for breaking news in real-time.

While Community Notes have provided a small buffer against false claims, their impact is limited. They can flag misinformation, but they can’t reverse the deeper issue: a platform once synonymous with news credibility is now seen as chaotic and unreliable. For better or worse, the cracks in X’s foundation have reshaped how we consume and trust information online.

All that being said, in a world where misinformation is thriving and journalistic boundaries have blurred, it’s no surprise that blind items have found fertile ground. Whether we’re aware of it or not, the line between verified news and rumours keeps getting thinner.

The normalisation of conspiratorial thinking in the digital world has intensified this even more — bringing us to our third theory behind the rise of blind items.

Over the past few years, we’ve witnessed conspiracy theories shift from fringe spaces to mainstream politics and pop culture. This shift didn’t happen in a vacuum; it resulted from several factors. One of the most frequently cited reasons is the rise of populist leaders like Donald Trump. His anti-elitist rhetoric and style have redefined how many people view authority, fostering an environment of deep scepticism toward established institutions and expertise. Combine this with the endless flow of misinformation online, and you have social media users who question just about everything they encounter.

Conspiracy theories, which once existed on the periphery of common discourse, are now firmly planted in the mainstream. Take Pizzagate as an example. This conspiracy theory exploded in the 2016 US election, claiming that members of the Democratic Party were involved in a child-trafficking ring. Although it has since morphed into the broader QAnon movement, it was originally amplified through platforms like 4chan, Reddit, and Twitter. While sites like 4chan remain niche, platforms like Reddit and Twitter have made conspiracy theories more accessible to the general public, pulling them into the mainstream.

Adding fuel to the fire is the role of influencers, some of whom actively promote conspiracy theories. While many of these influencers cater to niche audiences, there’s a more subtle, pervasive danger when mainstream creators dabble in this content. Consider Shane Dawson, who really solidified his online presence through the mid to late 2010s, with a mix of conspiracy theories videos and documentary-style videos. Shane’s content ranged from lighthearted speculation— like questioning whether Chuck E. Cheese reuses uneaten pizza slices— to more serious ideas.

While Shane’s videos were often framed as entertainment, they inadvertently normalise a conspiratorial mindset. By encouraging audiences to question everything, this type of content lays the groundwork for broader distrust of institutions and verified narratives. Even seemingly harmless conspiracies can push people down a slippery slope, priming them to believe unverified or blatantly false information.

But creators like Shane, who blatantly cover conspiracy theories for entertainment, are not always the most harmful. We tend to see more damage done by influencers who covertly support conspiracy theories and push that support to their audiences. Influencers in the health and wellness space are arguably some of the biggest culprits here and have long been criticised for spreading mis- and disinformation, encouraging their audiences to “do their own research,” ignoring advice from experts and professionals, and ultimately, introducing their followers to the well-established wellness-to-alt-right pipeline.

That being said, this cultural shift toward speculation and distrust has undoubtedly contributed to the rise of blind items. Much like conspiracy theories, blind items thrive on the idea of uncovering hidden realities, making them a natural fit for an increasingly sceptical and investigative audience.

And this growing scepticism amongst audiences leads us to the final reason we suspect that there’s such an interest in celebrity blind items– they feed into our negativity bias.

For anyone that regularly consumes blind items, you’ll be well aware that they often lean negative, focusing on upsetting or damaging information that can harm a celebrity’s career. People naturally gravitate toward negative news, as it tends to leave a stronger impact.

Negativity bias refers to our natural tendency to focus on “bad news.” It stems partly from our survival instinct to stay alert to potential threats and partly from a morbid curiosity about just how chaotic things can get.

Back in 2014, researchers Marc Trussler and Stuart Soroka at McGill University in Montreal ran a study that showed we’re more drawn to bad news than good. The reason being that deep down, it’s part of human nature to think our own lives are better than most.

BBC’s Tom Stafford, covering this research, explained it like this: “When it comes to our own lives, most of us believe we’re better than average, and that, like the clichés, we expect things to be all right in the end. This pleasant view of the world makes bad news all the more surprising and salient. It is only against a light background that the dark spots are highlighted. So our attraction to bad news may be more complex than just journalistic cynicism or a hunger springing from the darkness within.”

So, our fascination with bad news isn’t just about media spin or some inner darkness—it’s more nuanced than that.

This belief that we’re “better than average” is known as illusory superiority. Several theories try to explain why we see ourselves this way, but a big one is egocentrism. That’s where we focus more on our own skills, traits, choices, and actions than on anyone else’s.

When we consider the rising interest in blind items within that context, it becomes clear that negativity bias plays a role in this morbid fascination. Hearing gossip, drama, and bad news about celebrities feeds our ego, as these are people who are supposed to “have it all.” Western society has largely put the status of celebrity above all else – so hearing about how these people that we idolise don’t have perfect lives… that humanises celebrities and confirms our illusory superiority, making us feel like we actually might measure up to these people if it weren’t for different circumstances.

And the rise of TikTok over these last few years amplifies the interest in blind items, as content on TikTok is driven by high engagement rates which accounts can often achieve by sharing drama, gossip, or negative news.

The ethical implications of blind items

While there are surely other reasons for the rise of celebrity blind items that haven’t been covered here, there’s no doubt that this phenomenon– though admittedly very fun to engage with– comes with a host of ethical implications that we cannot ignore.

Aside from the obvious concerns around normalising information that is completely unvetted, the core ethical dilemma of blind items revolves around balancing the public’s right to information with an individual’s right to privacy.

This friction is even more amplified when we consider that the majority of blind items don’t necessarily fall under the category of public interest information, nor are the subjects of these blind items often granted the right to reply– which is a core journalistic principle– given names are usually kept anonymous. This lack of journalistic integrity when it comes to blind items adds to the public’s rejection of mainstream media and helps normalise the acceptance of unverified claims.

And of course, we couldn’t talk about the harm that blind items cause without considering how this type of content impacts the subject of these tips and rumours.

Though there is ongoing speculation that publicists and talent managers now submit tips about their clients to these accounts as part of a wider media strategy, the harm to the celebrity’s public image and their mental health no doubt cancels out any benefits of these accounts.

Given what we’ve explored, it’s clear that the ethical implications of blind item culture clearly represent a symptom of larger culture and social changes, and have, at least in some small way, contributed to the normalisation and acceptance of these changes.

As of today, there’s extreme distrust in mainstream media and those in positions of power. While a healthy scepticism of power structures is positive, trusting the claims of the online rumour mill can harm a media landscape that depends on trust to function. Being bombarded with unverified claims— many of which may be false— undermines fact-checked reporting and ultimately, can cause harm to those on the receiving end of these claims.

Listen to the full episode via the ‘infinite scroll podcast’ on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, and YouTube.